The Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument or TKI has been around since the 1970s and bills itself as the world’s most widely used conflict style inventory. I started out as a Thomas Kilmann trainer in the 80s and found it very useful. I got frustrated eventually and developed an alternative, for reasons I’ll explain. But for at least one purpose, you should still use the Thomas Kilmann.

The Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument or TKI has been around since the 1970s and bills itself as the world’s most widely used conflict style inventory. I started out as a Thomas Kilmann trainer in the 80s and found it very useful. I got frustrated eventually and developed an alternative, for reasons I’ll explain. But for at least one purpose, you should still use the Thomas Kilmann.

History of Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument

A concern of Ken Thomas and Ralph Kilmann in developing the TKI was “social desirability bias”, a phenomenon in testing in which test takers answer questions dishonestly. Rather than truly describe their own behavior, they answer in ways they think are socially desirable. Kilmann writes in his explanation of the development of the TKI that he and Thomas were inspired by their study of the Mouton Blake inventory, a predecessor to and paradigm for their own instrument. But the Mouton Blake had a glaring social desirability bias problem.

Kilmann observed a situation in which the Mouton Blake inventory had been administered to managers. From the way statements in the inventory were worded, he writes, “it was obvious that ‘collaborating’ was the ideal mode, while ‘avoiding’ was the least desirable one.” “Sure enough,” he continues, “that’s exactly how managers rated themselves, with over 90% ranking themselves highest on collaborating and lowest on avoiding. Their subordinates, of course, experienced those same managers very differently.”

Thomas and Kilmann set out to create a similar conflict style test that would be free of the influence of social desirability bias. They adopted the underlying framework of the Mouton Blake, but designed their conflict mode instrument with 30 questions containing paired statements, each worded to be equally desirable. Takers are asked to choose the statement in each pair that more accurately describes them.

Since 1974 when it was first published, good publisher support, ongoing engagement by the authors in how to use the TKI, and use of the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument in various research projects have propelled the TKI to a leading role.

Limitations of the Thomas Kilmann

So why look any farther? The following experiences with the Thomas Kilmann drove me to seek alternatives and eventually create my own:

1) The Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument frustrates many users. As a trainer I discovered that the forced choice question format of the Thomas Kilmann greatly annoys a significant number of test takers. Users are presented with two descriptions of responses to conflict and required to choose one of them.

In my own first experience as a test taker, I kept thinking, “I wouldn’t choose either of those options!” But I had to commit to one to get through the inventory. As a trainer I saw that in most workshops there was a least one and often several people so frustrated by the question format that they turned negative on the whole learning experience.

2) The TKI has a tin ear on cultural issues. Whenever I had people in workshops from outside mainstream white culture, I got even more criticism of the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode instrument from users distressed that some of the 30 questions forced them to select an option that didn’t fit them.

Years later, as my understanding of cultural issues deepened, I realized that the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument assumes what Edward T. Hall in his 1976 book, Beyond Culture, calls a low-context cultural setting. People from such backgrounds respond to conflict with minimal consideration of issues like role, seniority, status, etc. That assumption works for some test takers but not for those from cultures where the first question is not “what do you want?” but “who is the conflict with?”

For people from such high-context cultural backgrounds, an appropriate response to conflict cannot be contemplated without knowing, say, whether the conflict is with an elder, a peer, or a younger person. High-context culture people need context to answer questions about how they would respond in conflict, and are flummoxed by an inventory that provides none. Read more on that and how we resolve the issue in the culturally agile Style Matters inventory .

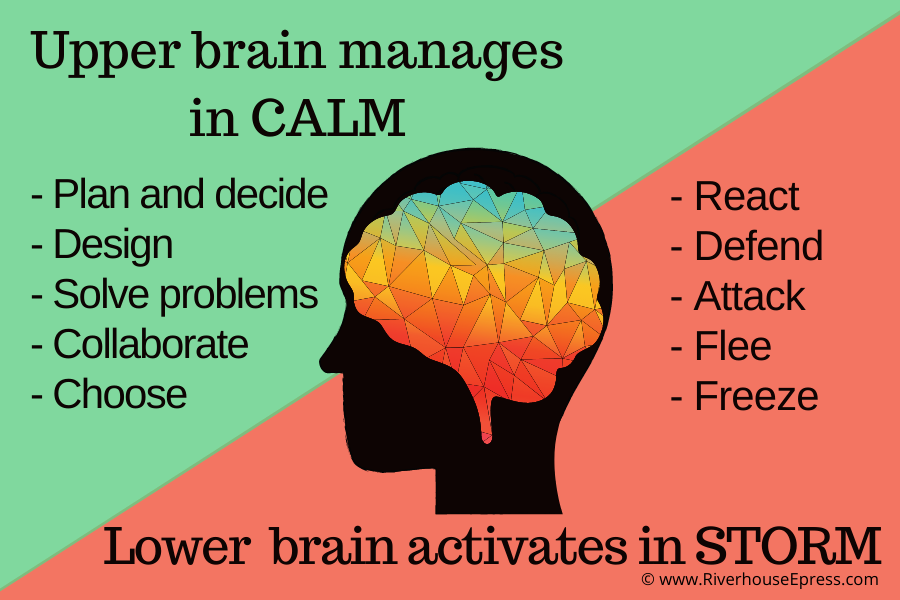

3) The Thomas Kilmann is blind to the impact of stress. The notion that human beings function in a steady state, an assumption of the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode profile and its interpretive report, is several decades out of date. We now know that when humans are angry, afraid, or highly stressed, our brain functions are increasingly influenced by the reptilian brain and decreasingly managed by the neocortex, the rational, problem-solving part of the problem.

When the reptilian brain is in control, priorities and behavior change drastically, towards survival-oriented, all-or-nothing, fight/flight/freeze responses. This means that in order to help people realistically assess their conflict responses, a conflict style inventory or test has to assess behavior in settings of both Calm and Storm.

In its interpretive report the TKI refers to primary and fallback style preferences, but that’s different than a stress shift. The transition from neocortex-managed functioning to lower brain-managed functioning is complex. Behaviors and priorities change, data processing ability declines. The data from Style Matters makes it clear that many users function quite differently in Storm than in Calm and that people’s use of several conflict styles often changes.

3) User support is thin. The TKI comes as a barebones unit with few interpretive materials. Trainers can lead a workshop, or buy supplemental interpretive booklets, but either way users depend on receiving additional materials to make sense of their scores. That’s OK sometimes but a pain other times.

4) TKI Cost is prohibitive. I’ve always done a lot of work in community settings where the hefty charge of the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument, $19.50 per user today, is prohibitive.

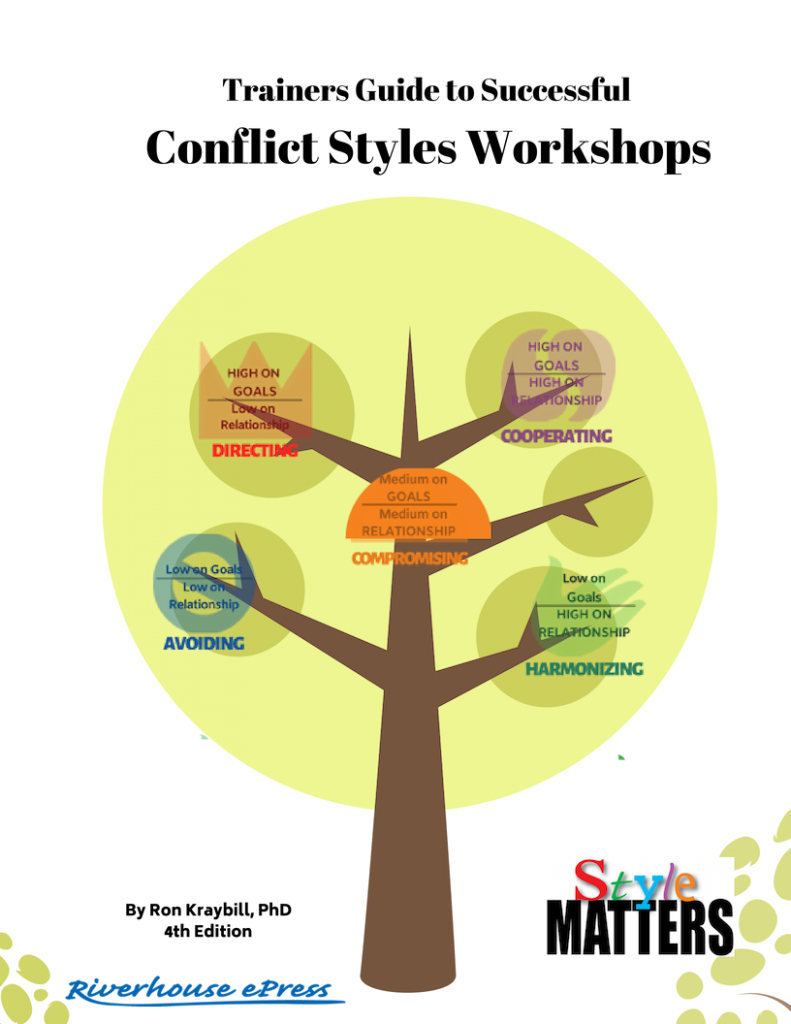

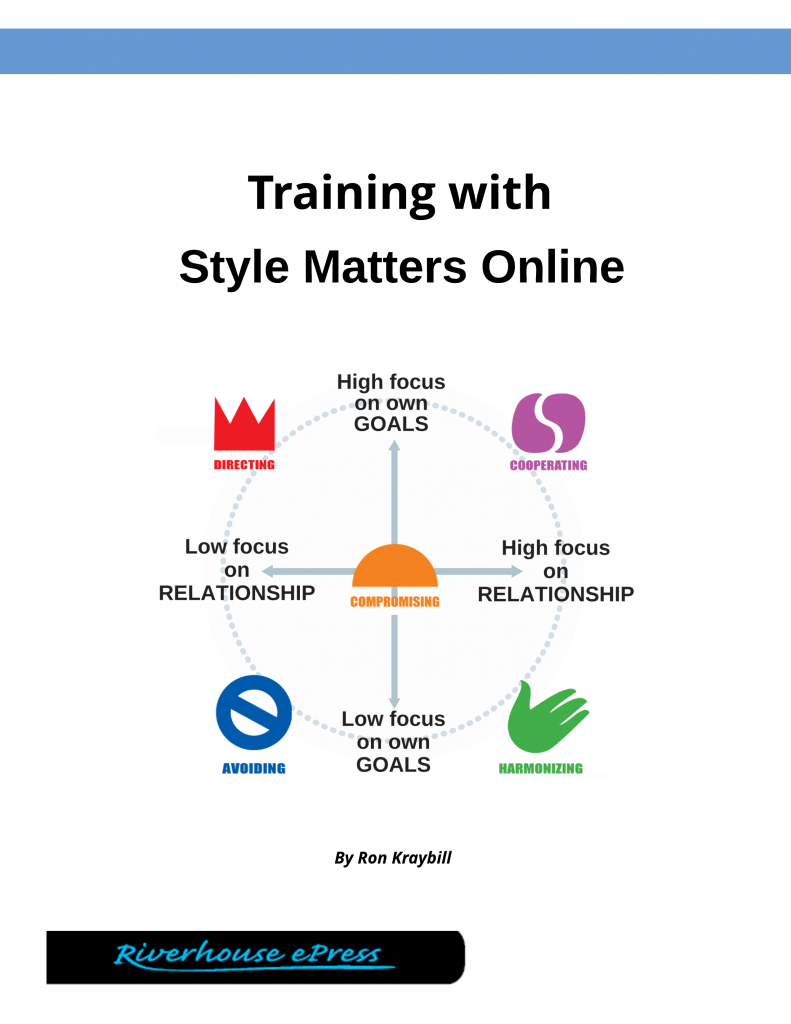

As a trainer, those factors weighed on me, and eventually I moved to create an alternative. Over 15 years of experimentation I developed Style Matters, which like the TKI, uses the Mouton Blake framework, while addressing those issues. Download a free review copy of the paper version of my conflict style here and view a sample score report of the online version here. See also our free Trainers Guide to Successful Conflict Styles Workshops.

What about Social Desirability Bias?

Thomas and Kilmann were inspired to develop their TKI in response to social desirability bias apparent in scores of takers of a predecessor, the Mouton Blake inventory. In his history, Kilmann says that 90% of users rated themselves as highest in Collaborating (Cooperating in Style Matters) and lowest in Avoiding in a workshop with the Mouton Blake.

With Style Matters, slightly less than half of users show that particular response pattern in Calm conditions. In Storm conditions, less than one-third report it. That’s predictable: Calm conditions are precisely the setting in which that pattern would be most appropriate and easiest to deploy, so it is predictable that this pattern will be favored by many people when their emotions are not yet aroused. That most of these same people report much less use of Collaborating/Cooperating) in Storm conditions reflects substantial candor. Those numbers don’t scream social desirability bias.

Style Matters achieves this by wording the questions in ways that highlight the value of each conflict style. In addition, Style Matters queries responses in two settings, Calm and Storm. This simple differentiation acknowledges the reality of stress and makes it easier, I believe, for takers to admit responses they may consider less than desirable. The numbers cited above show that many users report different behaviors in Storm than in Calm.

At the level of raw numbers, then, it’s far from obvious that our users are more vulnerable to Social Desirability Bias than those of the Thomas Kilmann.

Thomas Kilmann’s Theory of What Motivates Change

There’s an issue more important than social desirability bias that needs to be on the table as well, theory of change. The publisher of the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument, CPP, often advertises the TKI as having “rock solid metrics”. Never mind that the strategy employed alienates a lot of users, to select metrics as the defining quality of the inventory reflects an assumption about what facilitates personal change: Change and growth happen when people are confronted with a picture of themselves believed to be highly accurate and authoritative. This confrontation with reality will be eye-opening, the test designers seem to believe, and users will be motivated to change their behavior to be more constructive.

That’s an inadequate theory of change, in my view. Personal change doesn’t reliably result from a confrontation with authoritative numbers about yourself. It is more likely to emerge from a process of honest self-assessment, supported by thoughtful conversations, in a setting with sufficient familiarity and safety that people trust the learning process.

Getting an accurate picture of behavior from numbers on a test is good. But there’s something far better than getting it from a test: Reflection, that is, getting an accurate picture of your behavior from a process of ongoing personal analysis and conversation with others who know you well.

Reflection always trumps numbers as a motivator of change. In fact, reflection will facilitate personal transformation even in the absence of numbers on a test. But numbers on a test are useless in the absence of reflection.

The big question is how to get people to reflect deeply. As a trainer, my number one goal is for people who attend my sessions and interact with my materials to trust the learning process they encounter. Not necessarily “like it” in every aspect, but trust it. Trust that the materials and the learning process are relevant to their life, trust that they are respected and recognized as authorities on themselves, trust that the conversations with me and others are authentic and safe.

When such trust is present, all is possible in terms of sustainable learning and growth. When absent, all bets are off. To me that means that, in conflict styles training, if there are tradeoffs required, we should prioritize trust and learning environment rather than psychometric purity.

The Thomas Kilmann TKI can of course be used in processes that value trust and learning, but the instrument itself, in my view, detracts from that goal.

How Style Matters Contrasts to the Thomas Kilmann

Whereas the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument has been optimized for validity and reliability, the holy grail of psychometrics, the Style Matters Conflict Style Inventory has been optimized for the requirements of learning.

Rather than use a question format that alienates many users, Style Matters counters social desirability bias in ways that build trust with users. Even if that costs us something in the form of scores presenting an image of users that is somewhat rosier than reality (a big if – I see no evidence this is the case), I’d rather sacrifice accuracy than trust. We don’t need a perfectly accurate image of the user in order to achieve success in the learning experience (which I define as improved ability to respond appropriately in conflict). What we do need is deeply engaged, enthusiastic learners.

A priority on learning environment calls for a rich, interactive process of self-reflection and conversation with others. Style Matters, especially in the algorithm-generated score report delivered to users taking it online, is designed to facilitate this by providing feedback on numerous issues not addressed in the TKI. These include the difference between Calm and Storm responses, detailed attention to the least used conflict style and how to ramp up its use, the dynamics of style combinations, detailed suggestions on how to create environments friendly to the requirements of each style, and for trainers who avail themselves of this option, cultural dynamics of conflict response.

We’ve also invested a lot in equipping trainers to lead workshops that reflect the dynamics of thoughtful self-exploration and conversation with peers I’ve pointed to above. We provide free training materials on our site, including a detailed 40+ page Trainers Guide and a smaller manual for online trainers, as well as a free “Intro to Conflict Styles” in Powerpoint and Prezi. We also provide a free Trainers Dashboard with powerful user management tools for trainers, to reduce the time demands of basic tasks. We’d like to see trainer time invested in the learning side, not the technology side of workshops!

Expanding user learning to continue after the workshop has ended remains an area where I hope to provide more support to trainers. Ralph Kilmann’s piece on the topic, “The Three Day Washout Effect”, is excellent in addressing the issue in the presence of colleagues in an organizational setting.

But many people face a situation in which they are the only person who’s taken the inventory. So what options for ongoing learning and reflection could we offer them? I’ll be experimenting with several in a university setting in the coming months.

When to Use the Thomas Kilmann Instrument TKI

Although I think Style Matters is better suited to normal training purposes of most trainers and consultants, there is a purpose for which the Thomas Kilmann is superior: situations where psychometric data is indeed needed. The TKI has been the subject of many studies over its forty years of existence, so more data are available on it than Style Matters. Style Matters was subjected to validation study and revised accordingly, but our data is undeniably thinner.

For that reason, trainers working in situations where it is important to be able to compare scores of current users with scores of past users and draw statistically precise comparisons should use the Thomas Kilmann.

How to Get More Info Comparing TKI and Style Matters

View point by point comparison of the Thomas Kilmann and Style Matters here. Find ordering information for Style Matters here. See also this short Thomas Kilmann wiki entry, a wiki entry on conflict style inventories generally and one on Style Matters. Annotated bibliography on conflict styles resources on the web here.

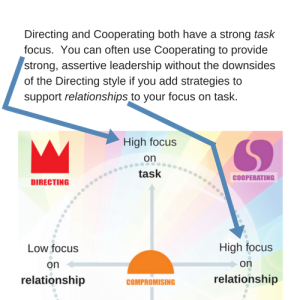

![]() But sometimes that’s not an option and you have to say something. This is especially common if you’re leading or coordinating a group of people.

But sometimes that’s not an option and you have to say something. This is especially common if you’re leading or coordinating a group of people.

provides detailed guidance on all aspects of conflict styles training, this short guide focuses narrowly on work with the online version of Style Matters. If refers often to the full guide, so you should have both.

provides detailed guidance on all aspects of conflict styles training, this short guide focuses narrowly on work with the online version of Style Matters. If refers often to the full guide, so you should have both.

and face-to-face training. But after Style Matters had been out in paper for several years, demand for an online tool drove us to also develop a digital version. That was an eye-opener for me.

and face-to-face training. But after Style Matters had been out in paper for several years, demand for an online tool drove us to also develop a digital version. That was an eye-opener for me.