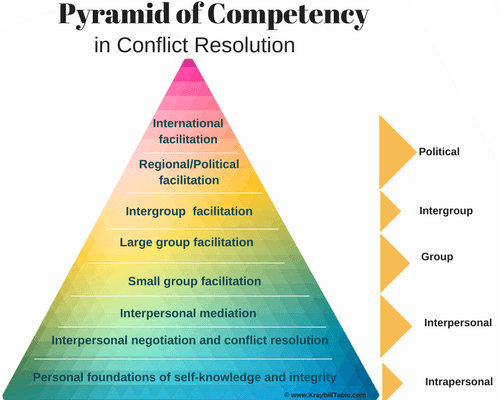

What is the connection between interpersonal conflict resolution tools like my Style Matters conflict style inventory or the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument and big conflicts of our world, like ethnic and religious violence or threat of nuclear war?

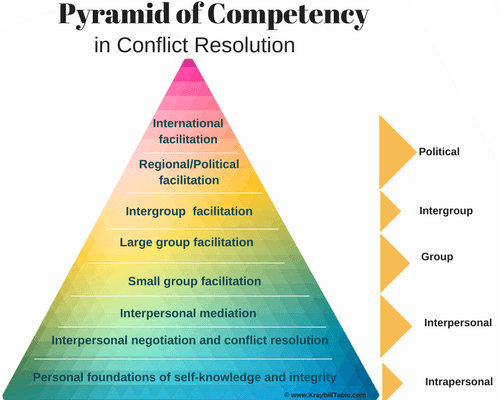

The Pyramid of Competency shows the many layers of competence required for addressing the complex realities of human relationships. I’ve used it throughout the world at the beginning of conflict resolution training to locate topics on a map of “the big picture”. I also use it in helping individuals eager to pursue skill development to chart a pathway for learning.

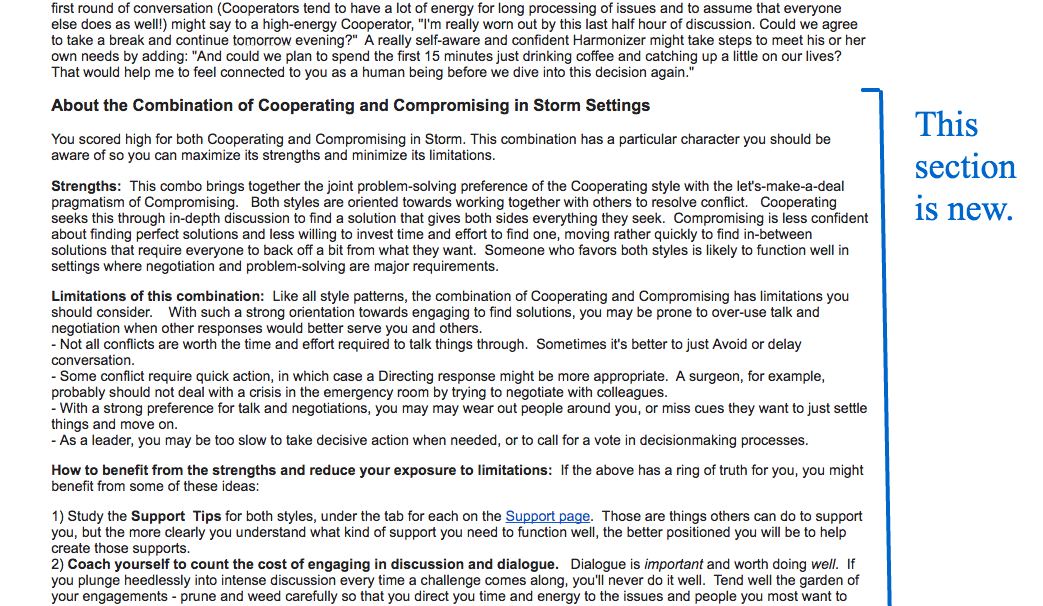

If you took my Style Matters conflict styles inventory or the Thomas Kilmann, you’ve already given some attention to the second level, “Interpersonal negotiation and conflict resolution”.

Ponder that diagram and you get some clues about why, despite all the progress humans have made, and all the institutions we’ve created, we’re still barely out of the Dark Ages with conflict resolution.

Conflict Competency is a Continuum of Skills

One of the most important things the pyramid shows is that conflict resolution competencies are inter-connected. To be consistently effective at any level, we need a foundation of skill at lower levels.

When you get good at one level, it opens access to the next higher one. I’ll illustrate this with my own career.

I spent early years after grad school establishing a new conflict resolution agency. I had little training for this – almost none was available in the 70s – and little experience. But thanks to good modeling of parents and elders in my life – and maybe to being the fifth of seven children, I had above-average abilities in interpersonal negotiation and conflict resolution. That was enough to get started.

Part of my job was mediating interpersonal conflicts. Although I had zero training for this, I read the few resources available and used my existing interpersonal skills to avoid disaster in early mediations. I was moving up the pyramid of competence!

As my mediation skills expanded I began to train other mediators. This gave lots of opportunities to develop skills in group facilitation skills. Up another level.

Gradually opportunities came to work with group conflicts. Although this was totally new territory, I was pleasantly surprised by how useful my now thriving interpersonal mediation skills were in group settings. I had mastered basics like starting off mediation with a strong beginning, setting a framework, listening well and getting input from those involved, asking good questions, reframing destructive comments, defining issues, exploring options, working out package agreements, etc.

Also, the long hours of leading training workshops had honed my generic group facilitation skills to a fine edge.

Facilitating group conflict processes required additional skills, for sure. But the solid core of skills from interpersonal mediation and the group facilitation helped me get through difficult moments while learning new skills on the fly.

I did early group work mostly in small group settings because my repertoire of skills in large group settings was quite limited. But that changed as I figured out ways to adapt the techniques and skills I was mastering in small group facilitation to the high-wire of large group facilitation, and add new ones learned from reading and discussion with colleagues.

After 10 years I was ready for a change and was able to arrange a position in South Africa at one of the country’s oldest conflict resolution agencies. My years of experience as a mediator, facilitator, and trainer in the US and Canada gave me skills desperately needed in a country entering a major peace process.

Soon I was appointed Director of Training at the Centre for Conflict Resolution in Cape Town and eventually as Training Advisor to the National Peace Accord, an organization mandated by the political parties to deal with the conflicts that brewed continuously around the on-going negotiations. Now I was drawing on and building skills across the entire span of the pyramid!

When Leaders Have Gaps in Competence the Cost is High

As in every peace process I’ve been close to, South Africa had plenty of people eager to assert leadership in its time of crisis. But few were skilled in facilitating discussion, negotiation, and decision-making processes. This made things vulnerable, like all peace processes, to one of the most poorly recognized dynamics of conflict resolution.

People think of peace processes as conflict resolution across a table between warring parties. It is. But it’s often conflicts behind the table that most endanger success. In South Africa far more people died in fighting among the various factions of the black liberation groups as talks dragged on than between blacks and whites.

Wherever there is a high energy initiative for change, whether a liberation struggle or reform of politics or institutions, there is conflict. Not only across the table between the predictable antagonists, but behind it, brother vs. brother. Just ask the Palestinians, the Syrian opposition, the ethnic minorities of Myanmar, or the US Republican party, to name but a few current examples!

Like leaders in every other sphere – whether business, religion, education, you name it – agents of change often have huge deficits in conflict resolution skills.

These leaders may be highly effective in maneuvering in upper levels of the pyramid, for example, where brokering power deals is essential. But for leading a staff meeting of colleagues, many don’t have a clue about facilitation practices, even basic ones that can be learned in a weekend workshop.

Or they get into vicious fights with people within their own movement who challenge them. They claim credit for things others have done, or opportunistically seize positions and power at the expense of their own colleagues.

The result is chronic frustration and blockage of processes among people serving beneath them and with groups who could be powerful allies.

Where such things happen it reflects the reality of gaps in competency in the lower levels of the pyramid, often the first three or four levels.

The consequences can be devastating. Movements of thousands or millions of people, constructed over decades, are sometimes shattered when organizations fall apart due to rivalries and resentments among key leaders.

My illustrations have been from the world of political change and conflict resolution, but it’s the same in most professions and sectors, whether education, religion, human services, or business. People in leadership may be widely esteemed for certain competencies. But many have huge gaps of competency in conflict resolution in levels beneath the one for which they are recognized.

Even Many “Peace Professionals” Have Big Gaps

A big reason why so many fires of conflict continue to burn unresolved throughout the world is because even in the structures of diplomacy and international conflict resolution, individuals with solid competencies in all the levels required are exceedingly rare.

I’m appalled by how many people I met in my years in the UN who carried mandates to support peace processes affecting millions of people, who clearly had no mastery of basic mediation and facilitation processes. Or who were driven by personal needs for recognition and control that deeply contradicted their professional effectiveness.

Expertise is Required at Every Level

Every family, neighborhood, institution, enterprise, community, region, and nation has to manage difficult issues. Even if outright conflict is not present, people have to talk things through and make decisions with others. People skilled in the competencies described in the pyramid are a tremendous asset in this.

To be serious about peaceful resolution of conflict, we need to train people at every level of the pyramid. Five hundred years ago the idea that everyone should be taught to read and write was laughable. Yet today we take universal education for granted.

Someday maybe it will be expected that everyone gets training in the basics of conflict resolution, and that portions of the populace will be trained in the higher levels of competency.

Can you imagine how different a world it would be if governments, political parties, religious organizations, businesses, medical institutions, etc., were led by people skilled in all the competencies corresponding to their position? When that day comes, we’ll remember today as the Dark Ages of conflict resolution!

Selfishness, envy, greed, ego, and other weaknesses will still be with us. But at least we will have a chance of reducing the consequences of our deeply rooted shadows.

Back to Conflict Styles Training

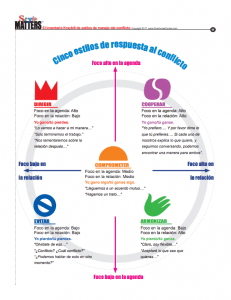

So where does conflict styles training fit into all this? As I pointed out in the beginning, it belongs with other rudimentary skills – like listening, basic conflict analysis, and effective confrontation – down there on the second tier. Such skills in interpersonal conflict are foundational, required by everyone and essential to success in all the other levels. If you’re not good at them, you’re going to perform inconsistently as a mediator, facilitator, leader, or president.

Conflict styles training is a great way to get people started on learning that can become an epic journey of preparation for higher levels of conflict resolution leadership. People learn about themselves in conflict styles training, but they also learn something else that is a new concept for many: Anyone can significantly improve their skills and tools for resolving conflict.

This discovery is enough to launch many people on a journey of expanding competency that lasts for a lifetime.

About Personal Foundations

The lowest level, personal foundations of self-knowledge, self-care, and integrity, is challenging. It’s hard to describe, measure and teach these things. They’re the product of a lifetime of struggle, reflection, and learning. All of us are deeply challenged here.

The schools and institutions currently training conflict resolution experts for various sectors are largely silent about this level. Little to nothing is said about the importance of inner maturity and wisdom. Training or support to grow on this level? Mostly zip.

I came to see this competency as fundamental through painful life experience. I was deeply disappointed by encounters with peacebuilders who were neither honest nor honorable. I was disillusioned by the dawning realization that in many conflicts the inability of peacebuilders to practice what they preach and work cooperatively with other peacebuilders is as big a block to peace processes as the dynamics between disputants.

I struggled with burnout and witnessed devoted colleagues severely handicapped by it.

So in designing a new Masters Program in Conflict Transformation at Eastern Mennonite University, I proposed to teach a course, “Disciplines for Transforming the Peacebuilder”. In the 10 years I taught it, many students said it was the most important course they took.

In the coming months I’ll be publishing essays from that course. If you share the conviction that this is an essential and poorly recognized element of preparation for conflict resolution, go to Settings for this blog now and make sure you’re set to receive posts on “Transforming the Peacebuilder” so you receive those posts as I send them.

Can We Afford All Those Levels and All Those Skills?

You might look at all those levels and skills, throw up your hands and say it’s too much.

Actually, it’s far from impossible. We don’t need to figure out anything new. We already know how to train people in every skill. The main challenge is simply that of building resolve to get institutions, schools, professions, and governments to do the obvious at a scale big enough to make a difference.

Those skills bring enormous benefits to those who use them. Listening, analyzing, and seeking creative solutions, which lie at the heart of conflict resolution, are central to human production and to the creation of wealth and social capital. People and organizations thrive when they are abundantly applied.

The benefits of systematically building skills of conflict resolution far outweigh the costs. The truth is: We can’t afford not to invest in them. Every day we pay – and dearly – for the costs of scarcity here.

What are you doing to change that in the realms where you have expertise, relationships, and credibility?

Ron Kraybill, PhD

www.kraybilltable.com

be productive and feel content with your job if relationships are rotten.

be productive and feel content with your job if relationships are rotten.

We can’t take collegiality and community for granted. We have to work steadily at renewing them.

We can’t take collegiality and community for granted. We have to work steadily at renewing them.