Sometimes you have to be pushy in conflict. Sometimes you have to say No and really mean it, insist that people step back, or lead in a direction some don’t want to go. If you are not able to do this, you may someday be taken advantage of or violated in ways that hurt and handicap you, for years.

Worse, you will someday fail to meet your responsibilities in a role you care about, like parenting, teaching, coordinating group activities, leading a team, facilitating meeting, exercising professional duties, or any number of other things important to you and your community. Success, health, even life itself, sometimes depends on someone being pushy.

But most of us prefer being nice more than being tough.

In this post, second in a series on the five styles of conflict, I’ll show you how to balance these two competing requirements. In particular, I’ll give you transition phrases for being pushy in challenging situations. These are phrases you’ve prepared in advance of stormy moments to help you gracefully initiate a conflict style you find challenging to pull off.

General Principles for Graceful Directing

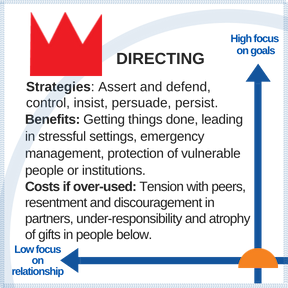

Directing involves pursuing a goal without be distracted or deterred by the resistance of others. There are many shades of Directing, since skilled people usually blend some other styles into the mix. But in its pure form, Directing gives high priority to a task or goal and low priority to relationships.

Wisely used, this “take charge” style has big benefits for certain moments. Over-used or badly used, it has big weaknesses, summarized below. This post is for when you’ve thought things through and decided Directing is the right response.

Be clear in your own mind about the necessity of Directing and come to terms with the role. Directing is not a particularly “nice” role. You’re choosing to ignore how others feel! But being able to use Directing is essential to living responsibly.

You can’t coordinate, administer, parent, teach, facilitate, or mediate well, without occasionally resorting to Directing. Sometimes the only right response is to be in charge, to be firm, to focus on achieving certain things without allowing yourself to be deterred by how others feel about it.

This is particularly true when we lead. It’s just not possible to please everyone. If two people both want to speak at the same time in a meeting, for example, we have to ask someone to wait, even though they might be unhappy about it.

Directing with grace is an art, best achieved from clear inner awareness of a legitimate purpose, larger than personal ego, that drives us. If you are at peace within yourself with the necessity of using Directing in the circumstances you face, you can find ways to lead, manage, supervise, or protect, as well as to disagree, challenge, and oppose that do not denigrate others.

Blend in relational styles whenever possible. Graceful Directing is about turning down the volume of your power to the lowest level necessary to achieve your goal, and blending in some relational styles like Cooperating or Harmonizing when possible.

You do need to be ready to amp up pushiness if required. But if you are skillful at blending in the relational skills typically associated with other styles and do so whenever possible, combat is rarely needed.

Many people seem to think effective Directing requires volume or anger. Once in a while, yes. But screaming drill sergeants and bellowing sports coaches are poor examples of effective Directing for most situations.

Those who master graceful Directing get important work done, set limits, make demands, and take charge, in ways that are relationally-oriented, even though the requirements of task and duty hold highest priorities. They are not always “nice” or accommodating, but even when they are non-negotiable, they are respectful towards others and they are careful to protect their dignity.

Pay attention to your non-verbals. Researchers say that 75-90% of communication is nonverbal. That means that the messages we send with body posture, tone of voice, eye movements, facial expressions, and hands matter even more than what we say in words.

So graceful Directing starts with waking up to your non-verbals. Most people are unaware of these, thus they don’t have a clue about the most important messages they are sending forth.

You can teach yourself to monitor your non-verbals, but it takes time. Welcome to the lifelong journey of self-management!

There’s no easy answer about how strongly to project your power. Some people habitually under-project, others habitually over-project. The key point is to get off automatic pilot and to pay attention to this aspect of yourself. Awareness puts a new tool in your self-management toolbox: Now you can turn the strength of your power projection up or down as needed, which increases your odds of success in interacting with others.

Transition Phrases for Graceful Directing

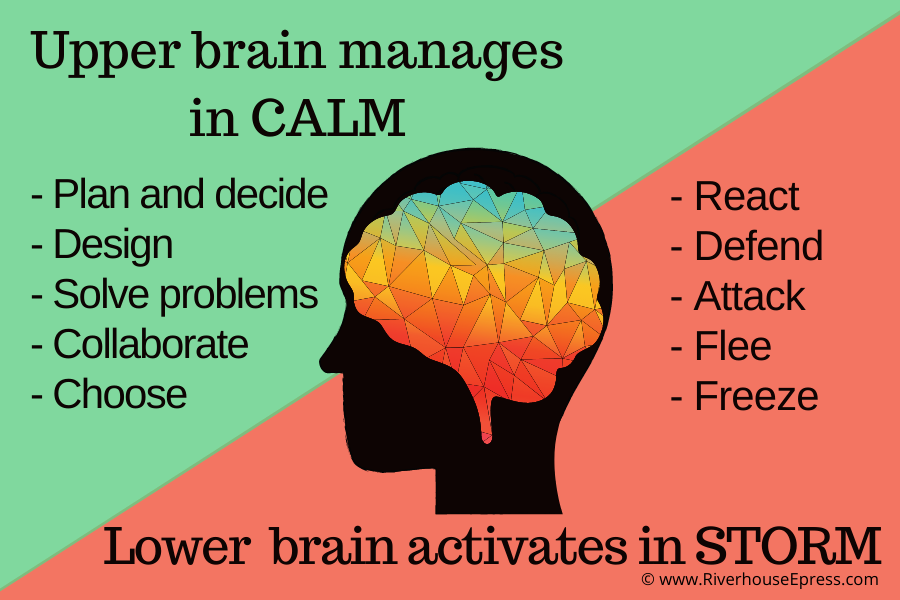

Why transition phrases? As conflict heats up, the part of our brain known as the reptilian brain becomes more influential. This brings primal, fight-oriented responses into the picture. As emotions rise, the lower, reptilian brain increasingly takes over from the upper brain, which coordinates communication and problem-solving. In the moment when we most need well-chosen words, the ability of our brain to formulate them is at its lowest.

A transition phrase assists in such moments. Phrases don’t magically fix things, of course, but they help get you started in the direction you’ve chosen, and learning them helps you think through valuable skills and responses. Learn several. Memorizing them is not a bad idea – so they’re on the tip of your tongue.

Provide information about what is needed. Except for emergencies (do you want the surgeon battling to save your life patiently explaining the strategy she has adopted to a confused team member?), the goal in using Directing should be to create maximum opportunity for winning compliance of others on the basis of understanding and cooperation rather than coercion.

The most effective strategy for this is providing information to others in a non-dramatic way. You will see that many of the transition phrases suggested below do precisely this.

Just fill in the blank after the crutch phrase with clear information about what you are requesting:

Please…

I’d like to ask you to….I would like you to….

Here is what we need you to do….

It would be helpful if you would…

It will work best if….

Our procedure here is that…

The rules require that….

I (we) would appreciate it if you would…..

It is important that (fill in the reason for whatever you require), so I need to ask you to….

I have quite a different understanding than you same to hold about this. Please review the facts (or rules, requirements, data, etc.). Let’s discuss it further after that if you’d like.

Whenever the situation allows, put effort into providing key info to the people involved in advance of a crisis or confrontation. That allows cooperative people – usually in the majority – to align with your plans and reduces the number of situations when you must use raw confrontation power to force people to comply. Clear signs, for example, facilitate the coordination of large numbers of people in public spaces without police needing to scream at everyone.

Acknowledge the other’s reluctance, then restate your own request. Sometimes, no matter how clear the info or how gracious you are, others disagree, or resist guidance. Sometimes, when we know that we have all the facts, when we know we are right, when we have a mission or principles or duties to protect, we have to push ahead, despite resistance.

Transition phrases for this could be:

I know this is not what you want, but we need to (whatever your demand is).

I’m sorry it’s inconvenient, but I’m afraid we need to stick with (the rule, the plan, the requirements).

I recognize that you’d prefer to do things differently, but (give the underlying reason, eg; policy, budget, precedent, etc).

I see/hear that you would like to do X (what the person wants to do), but I’m sorry to say that I need to ask you to do Y.

If you must escalate (assuming you’ve done your homework, and know you are right; but be aware that these may trigger a fight), options include:

Broken Record. Don’t get drawn into defending or explaining your demand, just keep repeating it.

Threaten consequences of non-compliance. But choose your threat carefully, remembering that a small threat often helps you more than a big one. If your threat is too big, you will hesitate to carry through on it and the other person will see your bluff. After that, all further threats have little credibility and you’ve weakened the usefulness of the strategy. The best threat is just big enough to have the desired impact yet small enough that you can promptly and easily carry it out, without second thoughts.

Go institutional. Every conflict exists in the context of groups and institutions such as families, teams, clubs, religious bodies, neighborhoods, organizations, businesses, etc. If you feel you must use Directing, it is likely the well-being of such an institution that motivates you. If not, examine carefully whether indeed this pushy style is justified.

Look for ways to draw on resources of wisdom and power from the group or institution seek to serve. You will probably need to do some homework on your own first. Talk to your supervisor, convene the elders or council, call a family meeting, review the bylaws or mission statement, study the guidelines, look at the organizational chart. If you face persistent, hardcore resistance, you need the perspective of others about how to respond. They can help you figure out if and how to invoke the power of the institution on behalf of the concerns you represent.

* * * * *

I’ve known a number of people in ordinary roles who I consider ninjas in graceful Directing. There’s the front desk receptionist in a primary school my children attended (I’ve known several special angels in this role!), the affable but no-nonsense manager of a local supermarket, the friendly but ever-competent project manager of a construction company, the sweet pediatric nurse who guided us firmly through a difficult moment, the productive farmer shepherding teenage children through an array of weekly chores, the head of a religious congregation renowned for her kindness who nevertheless runs council meetings with a firm hand.

These are people with demanding duties and responsibilities. They can’t say yes to everything that comes their way. They have to coordinate, manage, limit, and control all day in order to do their job well. They must prioritize certain tasks, obligations, and duties above pleasing people. We’ve all known individuals who manage such difficult roles by being tyrants. Perhaps they get the job down, but they make everyone around them miserable.

But Directing ninjas are so graceful that others experience them as relational people, even when the Director must turn up the volume of their assertiveness. The ninjas deserve hearing our appreciation, for many of them labor unrecognized; many don’t themselves recognize the value of the gifts they bring to the world. Notice what they do, thank them for their ability to assert and lead graciously, and learn from their example as you expand your own gracefulness with this challenging style!

.png)