Do you use an angry voice to communicate or give instructions when a firm, even voice would do the job just as well?

I witness this most commonly in sports settings, where it seems to be accepted that coaches and trainers shout angrily at those they are training. I’m not talking about raising the voice to be heard. I mean shouting with angry inflections and body language, to convey authority and motivate.

Sports isn’t the only place this happens. Every parent and teacher – and I speak as a veteran of both roles – gets ticked off at the youngsters in our charge sometimes. So do team leaders, managers, and supervisors of all sorts, working with all ages. Frustration comes with the territory of leadership.

Anger is a powerful tool for many good purposes, when used sparingly. The volume and intensity of anger say “Listen up…!” and often people do. When it’s exceptional, anger gets attention and underscores a message.

But used frequently, the positive effects of anger diminish. Anger stresses people. Eventually they tune out and turn inwards for relief from the bombardment. Then you have to shout louder for the same effect.

Worse, your emotional outbursts trigger similar responses in others. Drama and disrespect creep into many discussions and become normal. All communication suffers, frustration spirals, and morale goes down.

The Conflict Style Framework Offers Alternatives to Anger

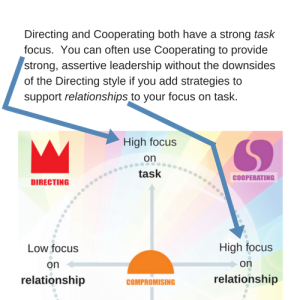

In the conflict styles framework, frequent appearance of anger in negotiation or leadership reflects over-reliance on the Directing style of conflict response. In the chart below, Directing is on the upper left and involves a high focus on task or agenda and low focus on relationship. An angry person is focused on getting others to do what they want, not on the relationship or how people feel.

That doesn’t sound very nice. But let’s be clear, that doesn’t mean this style is always a bad choice. If you can’t use Directing effectively, you’re going to let others down in a serious way. In order to protect youngsters from getting into danger, for example, every parent, every teacher, every youth leader needs to say “No!” at times and be ready to back it up with firm action. The focus in such moments is not the relationship, it’s on protecting others or upholding principles, even when this causes angry feelings.

People in all kinds of roles have a duty to place principle and duty higher than feelings and relationships at times. You don’t want the surgeon operating on you to negotiate with an assistant about procedures. You want firm, competent control by an expert professional who brooks no nonsense in getting things done right. They can patch up bad feelings later!

So hone your skills at this style. You will need it. But don’t make it a habit. If you do, it will begin to have diminishing returns and you will weaken the web of kindness and responsiveness that make organizations healthy.

Four Strategies to Reduce Reliance on Anger

If you recognize yourself in the category of over-use, you can take steps to get out of it.

1) Treat problems as information gaps rather than conflicts. As a mediator I am struck with how often big conflicts start out from simple misunderstandings. Had they been managed as such from the beginning and dealt with in calm, non-confrontational ways, many conflicts could be avoided. Things get polarize and escalate when you bring anger into the picture.

Treating problems as information gaps requires practice. Old patterns may pull you back to needless deployment of anger. To achieve the balance you seek develop these skills:

- Purpose statements. Use of clear, non-confrontational statements of positive purpose makes it easier for others to work with you rather than against you, even in circumstances that could easily turn confrontational. “I’m eager to get a good night’s sleep – would you mind keeping the noise down?” has a very different impact than “Do you have to be so loud?” Similarly, “It’s important that we stay together so nobody gets lost,” calmly stated, has a different impact than shouting “Stop lagging behind!” To create purpose statements you have to think through your underlying purpose and figure out ways to communicate it in positive terms. Until you get the hang of it, you will have to prepare in advance of difficult moments to pull it off.

- Clarifying questions help you interact with others in ways that invite and assist them to clarify their purpose and/or needs, without escalating an awkward moment into a conflict. There’s no catch-all formula for this, but consider these examples: “Sorry, what’s happening here is not what I was expecting. Can you help me understand this?” “I’m afraid I don’t understand what’s happening – can you clarify please what you’re trying to accomplish?” “Please say more about that, so I understand where you’re coming from….”

2) Expand your repertoire of skills for deploying influence and power. A common rationale for anger is that it is necessary to caution or block others from unacceptable behavior. But it’s not the only way to do that. Thought and preparation can often position you with different responses that don’t require any anger.

In mediation and group facilitation training, for example, we teach mediators and facilitators to call out rude behavior kindly, but firmly and early, as soon as it appears. If facilitators wait until rude behavior has multiplied, confronting it kindly is harder, for the facilitator’s own emotions have now increased.

With children, I learned that to achieve discipline without spanking or yelling I must lead by actively noticing and verbally appreciating good behavior as much as possible rather than only confronting the bad. I must take care to back my words with actions, never giving an order or threatening consequences I am not prepared to enforce. I must maintain on the tip of the tongue a series of clear and escalating responses to unacceptable behavior; my early responses must be small and simple enough that I don’t hesitate to use them.

Hospitals are a setting surprisingly vulnerable to intense conflict and hospital staff report violence-related injuries at rates far higher than other professions. To cope, many hospitals now train staff in de-escalation skills. One of these, in the words of one trainer is “calmly and firmly asserting the rules while acknowledging the other person’s humanity.”

Those examples aren’t comprehensive. The point is: Commit to an active quest to be influential and authoritative in ways that don’t depend on a turbocharge of anger. This takes time, thought, reading or discussion, and experimentation but the results can be transformative.

3) Use the Cooperating style of conflict resolution instead of Directing

In the language of conflict styles, the skills above enable you to use Cooperating as a response in situations in which you previously might have relied on Directing.

Directing and Cooperating are similar in that they share high commitment to Task. In using them we bring an agenda to engagement with others. We have a mission we feel is important to accomplish. We are assertive. This makes both Directing and Cooperating effective styles when we have a lot of work to get done, or a major responsibility we must fill.

But Cooperating adds something not present in Directing: major commitment to a relationship with those we are engaging. We pay attention to their feelings. We send frequent signals that we value them and their goals. We back up these signals with actions.

There is however a key cost you must reckon with in using Cooperating: settling on a solution takes longer and may demand more emotional energy than Directing. Unlike in Directing, you’re not just insisting on your own agenda, you’re paying attention to others, their feelings and views. There will be back and forth and a period of uncertainty as you wrestle with finding solutions that keep everyone happy.

There is however a key cost you must reckon with in using Cooperating: settling on a solution takes longer and may demand more emotional energy than Directing. Unlike in Directing, you’re not just insisting on your own agenda, you’re paying attention to others, their feelings and views. There will be back and forth and a period of uncertainty as you wrestle with finding solutions that keep everyone happy.

It’s not realistic for leaders to use Cooperating on every issue. But as others see that you use Cooperating whenever possible, they will be more accepting of those occasions when realities of time, budget, or other limitations require you to use Directing.

4) Circle back later, after moments when you have voiced your wrath, and take steps to signal care for the relationship. If you were over the top, why not acknowledge it? If the anger was appropriate, you can still signal care without compromising your principles by extending a gesture of warmth or appreciation.

I think many people who overuse anger under-estimate the damage their anger inflicts on relationships. Deploying anger has become so much a part of how they interact with others that they don’t see it as unusual or especially problematic.

Others can in fact cope with surprising amounts of anger if the over-user regularly takes responsibility to tidy up the mess afterwards. Just make sure it happens. Chronic failure to do such tidy up is deeply damaging to depth and trust.

My Style Matters conflict style inventory helps groups and teams engage in thoughtful discussion about their dynamics. Check out this infographic on two easy ways to invite users to take the inventory.