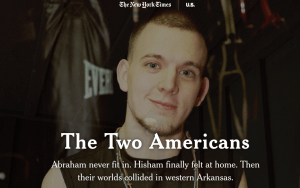

The NY Times carries a gripping account about vandalism by young whites against a mosque in Texas. One youth writes a heartfelt letter of apology and Muslim leaders are so moved that they request the judge to be lenient.

The prosecutor thinks this is a bad idea and forbids the youth from even visiting the mosque. Nevertheless, well, just read the story – you won’t regret it.

In a time when alienation is widespread, the response of NY Times readers to this story is one of visceral gratitude. Many comment it is the best they have read in a long time.

This is a story about restorative justice that Americans really need to hear. If we are to find our way back from the abyss of polarization, we have to stop planting seeds of alienation. This requires changes to a justice system that systematically blocks people from relationally-based responses to crime. .

The concept of justice widely known and applied in our society is court-centered  punitive justice, which holds no interest in healing of relationships or individuals. The court calls all the shots. The individuals involved have only small roles in the process, and no say in what happens.

punitive justice, which holds no interest in healing of relationships or individuals. The court calls all the shots. The individuals involved have only small roles in the process, and no say in what happens.

Victims often have the tiniest role and the least say in this process. They are expected to provide evidence of wrong-doing and then disappear for the court to mete out punish against an offender.

Restorative justice, in contrast, recognizes that offenses involve human beings and relationships and therefore responses ought to do so as well. It creates space for the instinct for healing that often still survives after offense and, when it emerges, allows it to shape sentencing.

Throughout the US, Canada, South Africa, Australia, and many other places, facilitators trained in restorative justice assist parties and justice system officials to work out a response to offense acceptable to the parties.

Restorative justice is not the right approach to all offenses. But it has grown rapidly since the early 1980s (first used by traditional and native communities; pioneered in courts in Ontario by Mennonite community workers in the 1970s; I did first US cases in Elkhart, Indiana in 1977; first US program there in the 80s) because it honors one of the strongest and best human instincts.

After offense we are hurt and angry. But we are also wired with deep knowledge that we ourselves are offenders at times and that offenders deserve support and help to grow.

If families, churches, mosques, schools, and courts would nurture this deep instinct, the polarization that threatens our world today would rapidly fade.

Stories like this help reclaim the best of who we are. There is hope! Share it!