[dropshadowbox align=”center” effect=”horizontal-curve-bottom” width=”700px” height=”” background_color=”#ffffff” border_width=”1″ border_color=”#dddddd”]Research shows that work groups of high power people do not perform nearly as well as groups of low power people. How can high power teams use more relational conflict styles and perform better? Here are seven strategies informed by the research.[/dropshadowbox]

Fact: High Power Leaders Do Not Play Nicely Together

So Grandma was right: Too many cooks spoil the soup. The title of a new study at Berkeley says it all:”Failure at the Top: How Power Undermines Collaborative Performance.”

The study finds that, although powerful individuals working alone perform tasks and demonstrate creativity at levels well above average, when they are required to work with other powerful individuals on tasks as a group, they perform well below average.

In the research, groups of less powerful people settled down and cooperated in tasks assigned to them. But high power people fought – over status, over who should be in charge, over who would have more influence over the group’s decisions, and over who should get more respect than others.

High power people also “were less focused on the task and shared information less effectively with each other than did members of other groups.” In short, the researchers found, “teams with less powerful executives reached consensus far more easily than teams with the high-powered executives.”

You can read the above quote in the NPR News site and hear an audio version below.

Maybe Grandma Knew, But She’s History

Do we need a study to tell us what we already know? One NPR listener to the above clip called the study a “blinding glimpse of the obvious”. “Thank you for wasting five minutes of my life,” he wrote.

Actually, the negative impact of power on collaboration is barely recognized and not at all understood. Otherwise, why would we continue to entrust the critical issues of our lives to groups of high power people on boards, committees, councils, and chambers?

Fresh out of several years in the UN, in posts with lots of face time with high power people, I assure you: Awareness that high power teams generally underperform is rare. Even more rare: people with a clue about what to do about it.

The American electoral and political systems threaten to implode because leaders don’t know how to get high power people to work together and voters seem oblivious.

Of course our system has checks and balances and many procedural safeguards. But systems can’t build consensus. Thinking, caring people have to put planning, time, and heart into the requirements of genuine collaboration, whether in organizations, communities, or nations.

But how?

Seven Strategies to Get High Power People Working Together

1. Provide clear assignments of roles, tasks, and mandates.

The study found that “groups comprised of high power individuals performed worse because they experienced greater levels of status conflict and used worse group processes. Specifically, groups comprised of high power individuals not only fought over status more but were less focused on the task and shared less information with each other.” (p280)

So when high power people are being launched on a task, reduce jockeying for power by defining and clarifying tasks, roles, and mandates in advance, as much as possible. That’s a no-brainer for groups of any kind, really. But with groups of high-power people it’s particularly important. For them an undefined structure is an accident waiting to happen.

2. Build recognition into the process.

Preoccupation with recognition and status was a dominating concern for the high power participants in the Berkeley study. You can say nice things about cooperating and deploy brilliant processes to assist it, but all is for naught if you neglect the basic human drive for individual recognition.

People squabble for power largely because they want to be recognized. Recognize this need, address it early, and address it continuously if you want collaboration to succeed. This applies to all kinds of people of course. But above all it applies to high power people.

Fortunately, recognition, like respect, is not “zero sum”. It can be easily created from countless sources and doled out generously to many people without taking anyway from anyone else. There are multiple ways people can play a role, make valuable contributions, and be recognized for these.

Yet high power people are stingy in recognizing others functioning as their peers. Left to their own devices, when it comes to recognition, high power people create deserts. Then, like thirsty bandits, they steal water from each other.

The antidote is pretty simple: build recognition of individuals, their work, and the contributions they think count into the process at all stages. This starts with basics like creating space at the beginning of work together for participants to properly present themselves and their involvements to others in the group. It continues by building in windows of time on a regular basis to update these.

Something else: Divvy out multiple leadership assignments within the group. Leading meetings and serving as nominal group leader are obvious leadership roles. But there are many more: information gathering, liasing with other people and groups, resource management, public relations, facilities arrangements, etc. Create a variety of meaningful roles, appoint people to them, and make sure no effort or result goes recognized.

3. Talk about process, early in the game.

The final sentence of the study concludes, “It appears that group processes are the major cause for failure when high power individuals must work together in groups.”

The process. Get the process right. As a conflict resolution professional of 35 years, much of what I do is a variation on this mantra. I’m often surprised at how poorly understood it is – except, of course, when people are themselves the disregarded in someone else’s bad process.

Funny how being marginalized seems to raise the lights on insights about good process. Even stranger: How gaining power seems to dim the obvious once again. .

Does good process guarantee peace? Of course not, but know this – bad process guarantees conflict and it is a rare day in the hinterlands to encounter tension in or between groups in which bad process was not perceived to be a key cause.

So what’s the right process? Probably several different approaches would work fine. The important thing is to talk about and agree on the process before you’re halfway into it.

Skilled facilitators lead groups in working out an “agreement on process” before diving into things. They agree on a definition of the issues or task at hand, on purpose or goals of the process, on the stages or timeline of the discussion, and on how decisions (by whom and by what percentage if voting) will be made.

4. Pay special attention to gathering and sharing of information.

A finding of the research is that high power people don’t share information as effectively in group work as low power people. Yes, lack of shared knowledge about the problem and possible solutions makes consensus a tad elusive!

A common mistake is to assume information sharing will happen on its own. That’s rarely the case in any setting and certainly not, the case study confirms, with high power groups. So special effort is required to encourage that which does not come naturally.

Designate a special time in meetings or a special phase in an extended discussion process for information sharing. Additionally, facilitators can help establish norms of information sharing by responding appreciatively when information is shared, holding this up as a model for others.

5. Use second tier negotiations strategically.

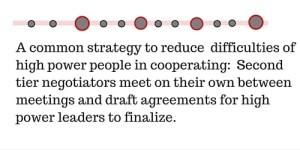

A story in NPR suggests an antidote to the squabbling of high power people: In political and international negotiations, underlings often meet on their own and hammer out a draft deal, before top leaders arrive and finalize things.

This puts the conduct of negotiation in the hands of people who are less powerful and thus generally have better instincts for cooperation – and greater skill in it – than high power leaders. In diagram form, that looks like this. Not bad, so far as it goes. But it fails to address another poorly recognized reality of decision making where power is a dynamic. An additional step is often required.

Not bad, so far as it goes. But it fails to address another poorly recognized reality of decision making where power is a dynamic. An additional step is often required.

6. Encourage “behind the table” talks.

Gaps in communication within each side are a common and poorly recognized block to consensus across the table. People focus on dynamics across the table and assume implementation will follow nicely once agreement is secured there. Warning signs of trouble within the ranks are overlooked, with the result that leaders are sometime blindsided by opposition from places they least expect, often just as success at the table appears imminent.

High power people chronically over-estimate levels of internal support and their own ability to bring subordinates into line. Odds are they will need to be nudged to invest the effort and time into internal consultation and consensus-building that will be required to enable agreements to move forward.

7. Build consultation with impacted constituencies into negotiation processes.

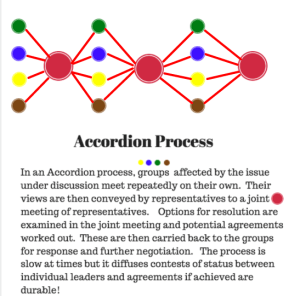

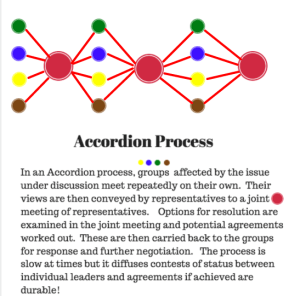

A common strategy about which David Straus and others have written is to design talks as an “accordion process”. Sub-meetings are set up – between sessions of high power people – in which groups affected by the issues under discussion are consulted.

An Accordion Process complicates some aspects of decisionmaking. But agreements achieved are more likely to be ratified and supported as a result. As a veteran of complex public planning processes in South Africa once said to me, “It’s going slow in order to go fast”.

In settings where large personalities overshadow all else, accordion processes help restore balance to group life and decisionmaking. They facilitate engagement, involvement, and thus ownership at multiple levels among diverse actors, thereby providing a corrective to the polarizing, self-aggrandizing, you’re-either-for-me-or-against-me style of some high power people.

High power, large personality people remain part of the picture, but their ability to swamp everything and everyone else diminishes. From accordion processes emerge fine, complex webs of diverse relationships that activate a large range of human capacities essential to healthy societies.

Not nearly all issues and decisions merit the level of attention provided by Accordion processes. But selective use on a regular basis brings many rewards in the form of enhanced group morale, expansion of skills for collaboration, and ultimately, greater quality and efficiency of decisionmaking.

Just as important, Accordion processes bring home another realization. Besotted by the empowerment that comes with life enhanced by devices tuned to our every individual want, modern people live in danger of losing an important awareness: We are not only one, we are many.

When communal structures are neglected and languishing, life as individuals is wretched. When connection and common purpose with others are lost, existence has little meaning.

And when people experience connections so rarely, how can we blame them for not bothering even to try to attain it? Strong processes do more than improve group performance. In giving a taste of the possible, they shape the vision and hopes we pass on to those who follow.

Signup for blog posts by Ron Kraybill on the intersection of conflict resolution and human potential in the right margin of this post or click here.

Ron Kraybill, PhD, has worked as an in-residence peacebuilding advisor and trainer in South Africa, Lesotho, the Philippines, Ireland and other locations for the United Nations, Mennonite Central Committee, and other organizations since 1979. He currently resides in Silver Spring, Maryland, and blogs at www.KraybillTable.com. Copyright Ron Kraybill 2016. All rights reserved. May be reproduced so long as this statement of authorship is included and links are made to www.KraybillTable.com