If you’ve already spent time with relatives this holiday season perhaps you’ve discovered things are not all fa-la-la at family gatherings. Getting together is great, but it can also bring conflict. All that cozy togetherness gives space for old issues to appear in new forms.

In a year when politics has polarized, more rancor than usual is likely to get served along with the turkey. Here’s what you can do about it.

Start with a resolution to be nimble at conflict avoidance. You can’t stop others from being pissants, but you can decline to be baited. Avoidance is a great conflict style for situations where you don’t have any real goal other than staying out of difficulty.

You probably already know which people and circumstances can handle candor and which cannot. Prepare lines for conflict harmonizing and avoiding that you can easily pull out when needed. To that annoying relative who can’t resist a verbal poke about politics or some other dicey topic, come back with responses that re-direct or de-escalate.

– “You know, I promised myself I’d stay on safe topics this year. Tell me about your new job….”

– “That’s a topic a little more lively than I’m up for right now. Want to hear what I did for the Thanksgiving holidays?”

– “I know you weren’t thrilled about my choice to XXXX, and probably neither of us is going to change our mind about that. But tell me, what’s going on in your life these days?”

You don’t have to be witty or cute to succeed with a conflict avoiding response. You just need to be firm in redirecting the topic. You’re more likely to pull it off if you’ve given forethought to the actual wording of your redirect.

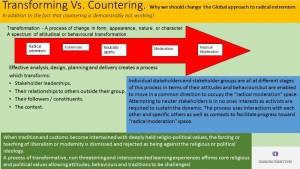

Perhaps the most important preparation you can do is update your personal boundaries before the holiday gatherings begin. Boundary maintenance is about recognizing that you and I are different people, each responsible for our own self, each respectful of the other’s independence. When we each have good personal boundaries, there is no emotional drive to change the other. You are you; I am me; we let each other be.

If I have healthy boundary maintenance:

– It’s fine for you to prefer a different politician – that’s your choice.

– Whatever choices you’ve made about your life are fine. They’re your choices, not mine.

– Your opinions about my choices and views, whether in politics, lifestyle, dress, career, etc., are simply that, opinions. I make my own choices and accept that you make your own. Just because someone doesn’t like my choice doesn’t mean I have to defend it.

– Your opinions about my choices and views, whether in politics, lifestyle, dress, career, etc., are simply that, opinions. I make my own choices and accept that you make your own. Just because someone doesn’t like my choice doesn’t mean I have to defend.it.

If I have poor boundary maintenance

– It’s hard for me to allow others to hold views different from my own.

– I am easily upset by choices you’ve made for your own life. I have a need to convince you that your choices are wrong if they don’t fit my beliefs.

– Your opinions about me and choices matter hugely to me. If you don’t like my choices and voices, I am upset and anxious.

Small children have no emotional boundaries and as a result are easily stirred to intense emotional responses by criticism or differing opinions. Boundaries develop and grow stronger in adolescent and adulthood, but maintaining and expanding healthy boundaries is a lifetime challenge.

A large number of people in mid-life and beyond have never developed strong boundaries. Family gatherings seem to bring out the worst in bad boundary management. When that happens people interact on the basis of old boundaries of long ago, as though they’d never grown and matured since the original years of being family together.

Updating your personal boundaries is the best protection against such dynamics. Staying connected to family members in a relaxed way over time helps that to happen. Being in touch as we grow and change across life helps us to learn new patterns of interacting that reflect our unfolding life as adults.

You can do a simple reflection exercise in a few minutes that helps prepare you for relaxed interaction with family members. The exercise guides you in reflecting on how you have changed and grown since childhood and teenage years.

Draw the diagrams below on a sheet of paper.

Then fill in some names. Start with your life at age of twelve and fill in the names of people in your family and network of friends who had a big affect on your daily sense of the quality of life. Then in the second diagram fill in names for today.

I’m not talking about distant people. Names in these lists should only be those people where there’s a personal connection and who have enough of a role in your life that a bad day or a bad month for them made (or makes) your life significantly harder.

When you are done, compare the two. Notice and appreciate fully the extent to which those two lists differ. For most people the lists are very different.

Take the exercise a step farther by listing personal strengths, talents, abilities, or accomplishments that have emerged in your life since the time you left your nuclear family. When you feel secure and grounded in these, you are less vulnerable to being suckered back into the vulnerabilities that every child lives with by virtue of being a child.

When we get together for holidays, we return to relationships of long ago. But of course we’ve lived and grown since. We now have resources of knowledge and personal foundations from other relationships and roles that did not exist in the old days. If we keep our inner sense of boundaries updated, we draw strength and stability from our recent life experience. We are less vulnerable to difficult dynamics from long ago.

But if we’ve failed to update our sense of boundaries, we react emotionally from the limits of our ancient self. We’re like twelve year olds (or whatever age that we suffered the greatest difficulties with the people we are interacting with) in adult bodies.

You can prepare for re-connecting to complex relationships by refreshing your awareness of who you are today. When your brother/parent/aunt/grandparent makes a move that pokes your emotional buttons, remind yourself of your current reality. Odds are high that the person has little to no capacity any longer to have any impact on your daily life, so long as you keep your focus on your current network of family and friends.

Spare yourself the energy required to react. Just let it be like water off the back of a duck. Shrug, grin, smile. Change the topic. Find someone else to talk to. Resist the temptation to try to change that person or fight back – if you do, you are already participating in the old patterns.

Draw strength from knowledge of who you are today and where you get the energy and joy that make your life meaningful.