Principles of Anger Management

What to Do When You're Angry

No matter what your conflict style, conflict brings anger. So anger management is an essential part of conflict management. Some guiding principles:

1. Anger is not the issue. How you manage it is what matters.

Anger is an emotion everyone experiences. Don’t wish it away – it provides resources essential to self-protection and survival. Its key resource is ability to respond quickly - with high energy - to threatening situations. Our goal should be to manage anger so its energies are directed constructively. We do this more easily if we consider it an ally requiring careful mobilization rather than an enemy to be rid of.

2. Some people express anger externally, others direct it internally.

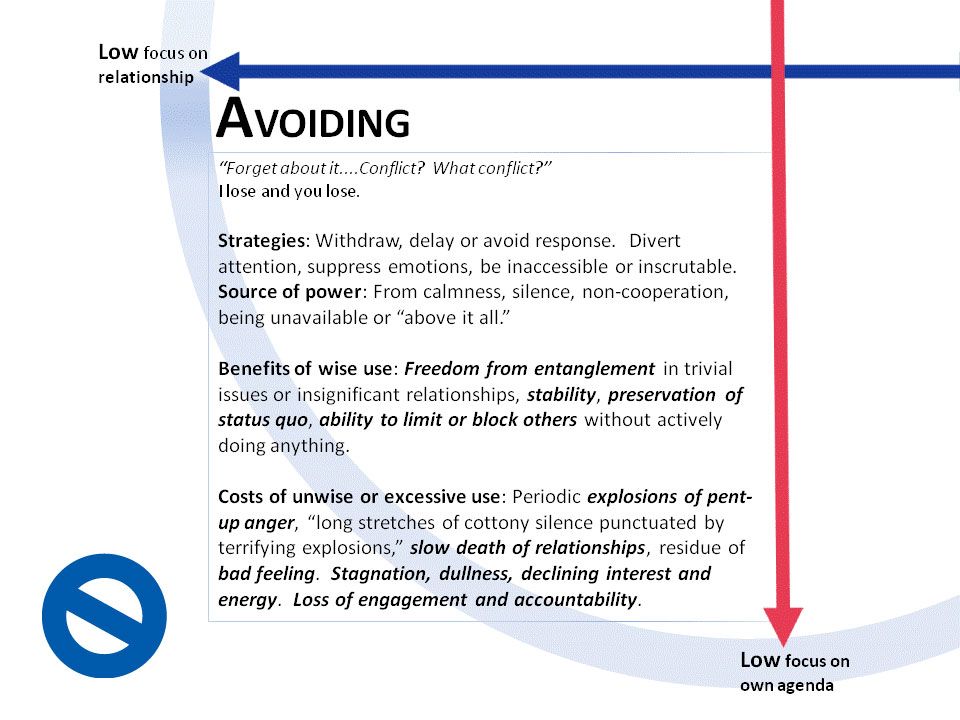

Anger that is externally expressed is easy to see - lots of noise, quick movements, and aggressive energy. Its dangers for relationships, emotions, and health are obvious. Anger directed internally is less visible, but carries large dangers of its own: chronic anxiety leading to stress-related illnesses and depression, relationships that die a slow, quiet death from distance and apathy, loss of hope and energy as people give up on things; periodic explosions when anger cannot be contained inside. If we only shut off or quieten expressions of anger we simply exchange one set of difficulties with another. The goal is healthy management of anger.

3. Anger is a secondary emotion.

There is always another emotion that comes before anger. Learn to be a good detective in uncovering what that emotion is, for when you can name it, you will move to a new level of self-management. Ask yourself – what other emotions do I sense here?

A clue: fear in one form or another lies behind almost all anger. Fear of injury, loss, or abandonment, fear of loss of autonomy or control, fear of embarrassment or exposure, etc. Most people are more in touch with anger than with their fears. After all, the heat and energy of anger is more life-giving than the cold paralysis of fear. And because anger rouses and activates, it has greater capacity to assist survival. But anger can easily crowd out attention to less noisy underlying issues. Anyone can learn to recognize the deep roots of their anger and, perhaps for the first time ever, position themselves to address it.

As you develop awareness of this primary emotion, work to understand it. Ask yourself:

- What sensations in my body do I associate with this emotion? (queasy gut, tight shoulders, sweaty palms, etc.)

- Where, when, with whom have I experienced this emotion in the past? Almost always, the emotions that trigger badly managed anger have their roots in experiences of childhood or youth.

- How did you deal with that past experience?

- What resources do you have today that you didn’t have or didn’t use back then?

- Some tools you can use to put that ancient experience to rest:

- Write a letter to someone who helped create the original fear. From a place of strength express your outrage. Do not send it; keep it for a few weeks, and when you are ready, destroy it.

- Write a letter of solidarity from yourself of today to yourself as you were in the original experience. File it, at least for a few months.

- With an understanding partner, roleplay a conversation with the source of your original anger.Be outraged and speak from a place of strength in the roleplay.

Recognize strengths or benefits that emerged in you as a result of that experience: grit, endurance, understanding, etc. No, this does not mean what happened was OK. It means rather that you are honoring your ability to not be completely defeated by hardship. Oddly, honoring strengths developed through hardship helps us rise above the past.

4. Self-awareness is key to anger management.

Anger is a problem when we are not able to make conscious choices about what to do with it. A rewarding path to anger management is simply to increase our ability to recognize its presence in us and our response to it. The suggestions in point 3 above can help do this. When we can consciously recognize the physical sensations that accompany anger, we make better choices about what to do with our emotions.

Some great tools for this are found in Buddhist literature, which sees lack of awareness as the primary obstacle to spiritual growth. Pema Chodron's "Don't Bite the Hook", for example, suggests that our inner response has "a familiar smell, a familiar taste" that we can easily learn to recognize. If we catch it early enough, she says, we can direct our response before it overwhelms us.

Mike Fisher, founder of the British Association of Anger Management, says anger is a defence mechanism against pain, and has produced a series of short, to-the-point free videos looking at anger from this perspective. (For fast reading, see the transcripts of the videos on that site, beneath the viewer) Some of these are for dealing with our own anger, some for dealing with the anger of others.

If you struggle with anger, seek greater awareness of the influence of pain, past and present, on your thoughts and emotions. Such awareness won't alone make the pain go away, but it can increase your ability to avoid being controlled by your pain. If you are hurt by the anger of others, you may find it empowering to consider them as individuals struggling - not very successfully - against deep inner pain.

5. Healthy expression of anger means talking about your anger without being aggressive.

Recent research shows that expressing anger in an angry way feeds the problem. You can talk about your anger without yielding to the impulse to be aggressive or to hurt others. Say that you are angry, say why you are angry, say what other people can do to help improve things - and say these things without being hurtful, hostile or rude. If you cannot yet do this, limit your communication when you are angry so you reduce the damage to others. Follow up with talking after you have cooled down, and use the cool-down time for detective work in preparation (see 3 above) or to review communication skills that might be useful.

When you talk, a formula that often helps to frame things in a non-aggressive way is the “I message”: “I feel….when you…. because…” A similar tool is the “Impact statement”: “The impact of what you do on me is the following….”

You are more likely to have a successful experience in this conversation if you agree on a way to structure it. For example:

- Use a “talking stick” and agree that you will pass it back and forth as you speak.You can speak only when you are holding the talking stick (pen, pillow, book, etc.)

- Agree on a sequence to organize the conversation, such as: “We’ll begin by giving each person 5 minutes to explain without interruption what they are upset about. Then we’ll try to list the issues where we disagree. Third, we’ll see if there are points that we agree on. Fourth, we’ll return to where we disagree and try to resolve those.

- Agree to ground rules. For example, agree that each person needs to repeat back in their own words what the other person has said, to the satisfaction of that person, before responding.Carry this structure for at least 15 minutes into the conversation, and agree when to relax it. The pattern is: Person A speaks, Person B repeats back. Person B speaks, Person A repeats back. Repeat and continue.

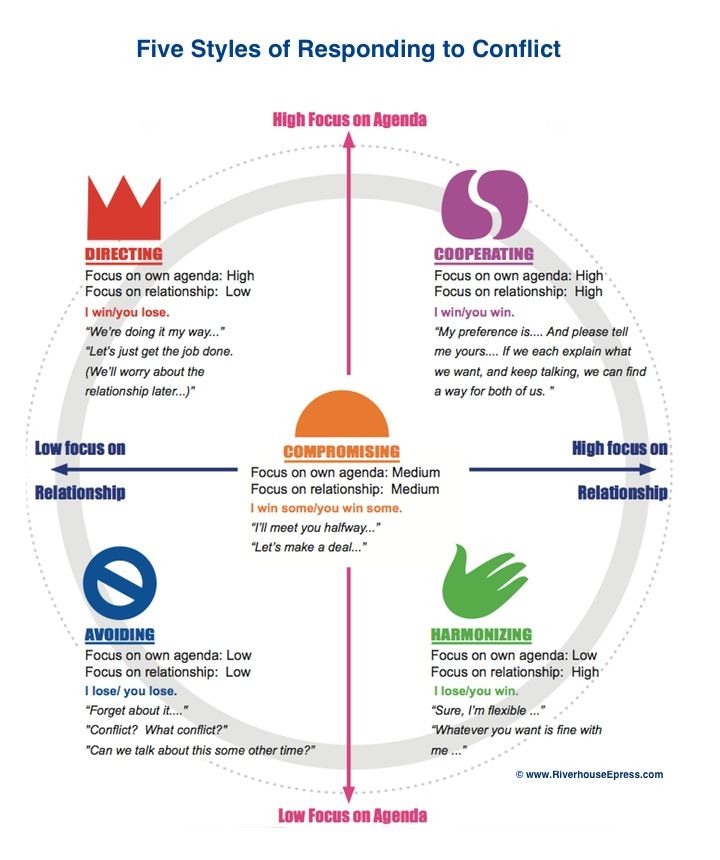

6. Conflict style awareness is a simple and powerful tool for self-management.

When you recognize there are at least five different ways to respond to any conflict you expand your options and increase your chances of responding constructively. Comedian Craig Ferguson says that he has learned, when he is angry, to ask himself three questions:

1) Does this need to be said?

2) Does this need to be said now?

3) Does this need to be said now by me?

That's actually a simple strategy for conflict avoidance, often a good short-term choice if we or others have difficulty with anger management. Similarly, remembering that there are skills we can use to find solutions that meet the needs of both sides may help us to invest the energy required to cooperate in exploring the needs of both sides.

7. Make things right when you cause harm.

Hurting others is an inevitable consequence of poorly managed anger. Fortunately, most people get over such hurt pretty quickly if you are diligent about cleaning up the mess you’ve made. Apologize, without condition. Not a cowardly “I’m sorry if I hurt you…” or a whiny, blaming “I’m sorry I said that but you were the one who started it…”

If you’ve done harm, be courageous and admit it openly, take responsibility for your own actions, and give the other person space to recover at their own timing. "What I said was hurtful and exaggerated. I hurt you and I’m sorry.” Know that people move at differing speeds to the point of readiness for such an exchange.

A critical point: Timing is everything in apologies, so do not rush the process. A hasty apology is often understood by others as – and ofen is - a polite form of shushing, a way of sparing the apologizer the effort and stress that comes with hearing a full articulation of the painful consequences of their actions. It also positions the apologizer one convenient step away from grabbing the role of wounded one, as in “But I've apologized, so why are you still angry!” Offered as a hasty reaction or as a demand for forgiveness, apology may in fact be a mechanism for evading responsibility. At the very least, a too-hasty apology is likely to be perceived as such.

Apologize has the most transformative effect after someone who is wounded has recovered a bit and no longer at a peak of frustration. If you caused the wound, consider a double apology – the first may be early and brief, just enough to signal your spirit and intentions. The second one may come later, after the other person has recovered composure and is ready to forgive. And of course sometimes it is a good idea to ask the one you have hurt: "I want to let you know that I am sorry about what I did, and I want to say this to you when you are ready to hear it. Is this a good time or shall I wait?"